When you start building a lot of Flows, you’ll start noticing that only checking values and if the actions succeeded only takes you so far. You would need better strategies so that you’re sure that the flows that run in production are as resilient as possible, or if they are not, at least you get notified so that you can fix the issues.

I wrote about this in the past in my “Try, Catch, Finally”, but I wanted to detail some more advanced patterns like automatic retries with exponential backoff, error logging for troubleshooting, graceful degradation when non-critical actions fail, and proper cleanup regardless of success or failure.

I will try to make things as approachable as possible (as usual) and explain the concepts. My main objective is that you understand the concepts their advantages and then decide which ones are useful in your daily Flows.

Let’s begin.

Configure Run After

The foundation of advanced error handling is understanding “Configure run after.” By default, actions only run if the previous action succeeded. This default behavior means the first failure stops your flow completely, and you’ll get an error message.

“Configure run after” lets you specify exactly when an action should run:

- is successful (default): Run only if the previous action succeeded.

- has failed: Run only if the previous action failed.

- is skipped: Run if the previous action was skipped due to conditions

- has timed out: Run if the previous action exceeded its timeout.

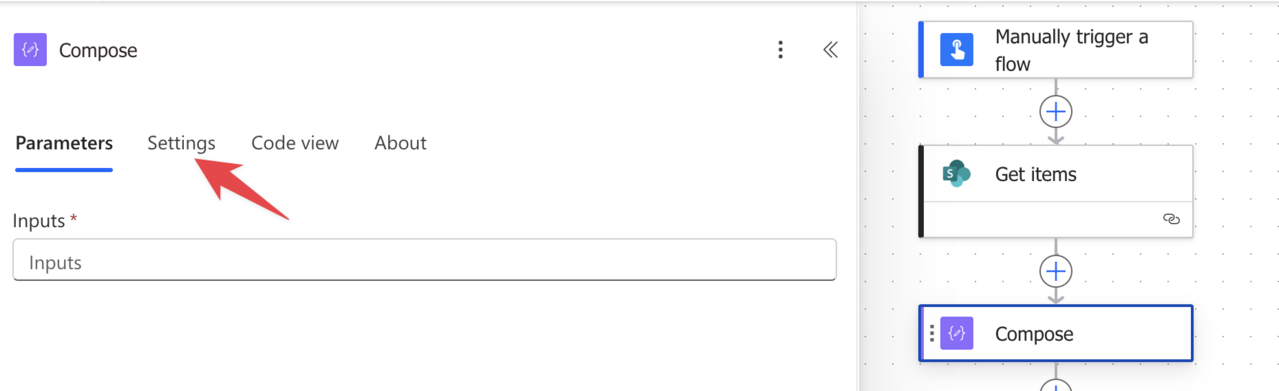

It’s easy enough to find it. We’ll use the “Compose” Action after a SharePoint “Get Items” action. The actions are not important, just for us to see what’s happening.

We’ll pick the “Compose” Action and access the “Settings”:

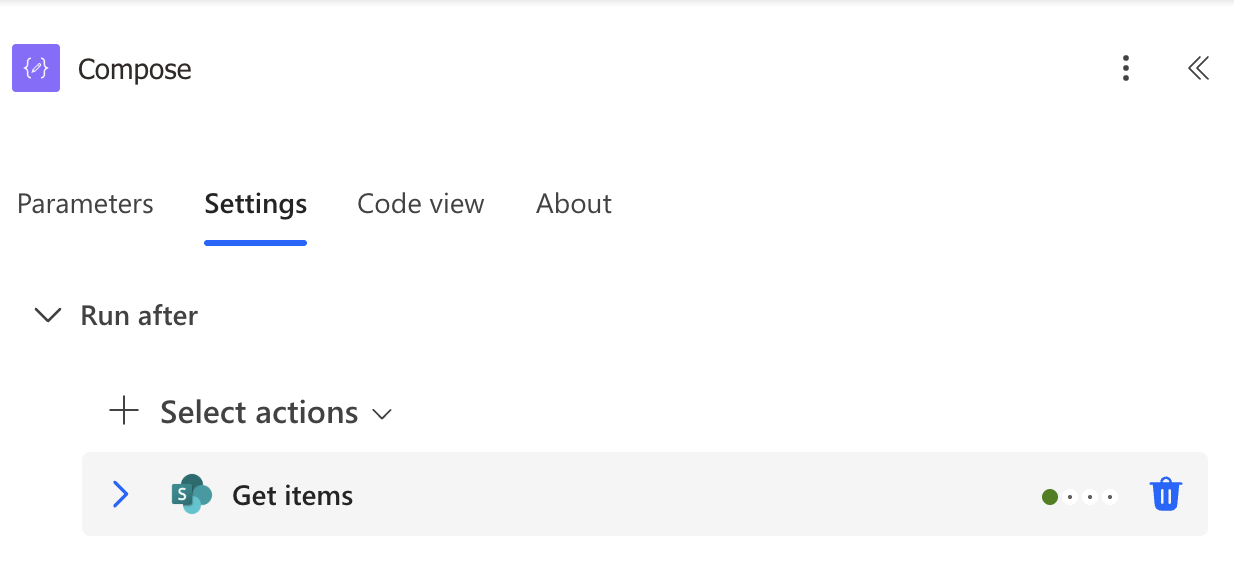

Then you’ll see the actions. In this case we have the “Get Items” action.

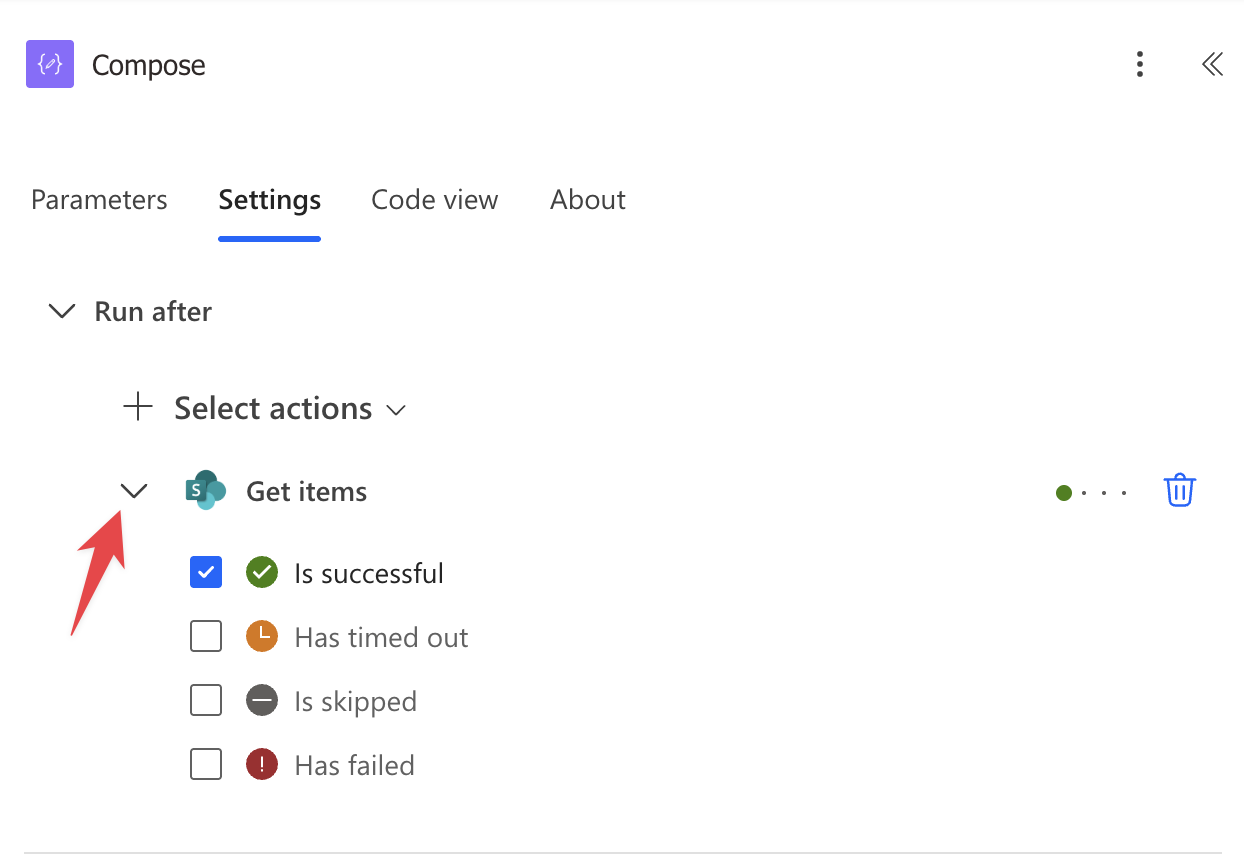

You can expand and will see the default “Is successful” option, meaning that the “Compose” Action will only execute if the previous one is successful.

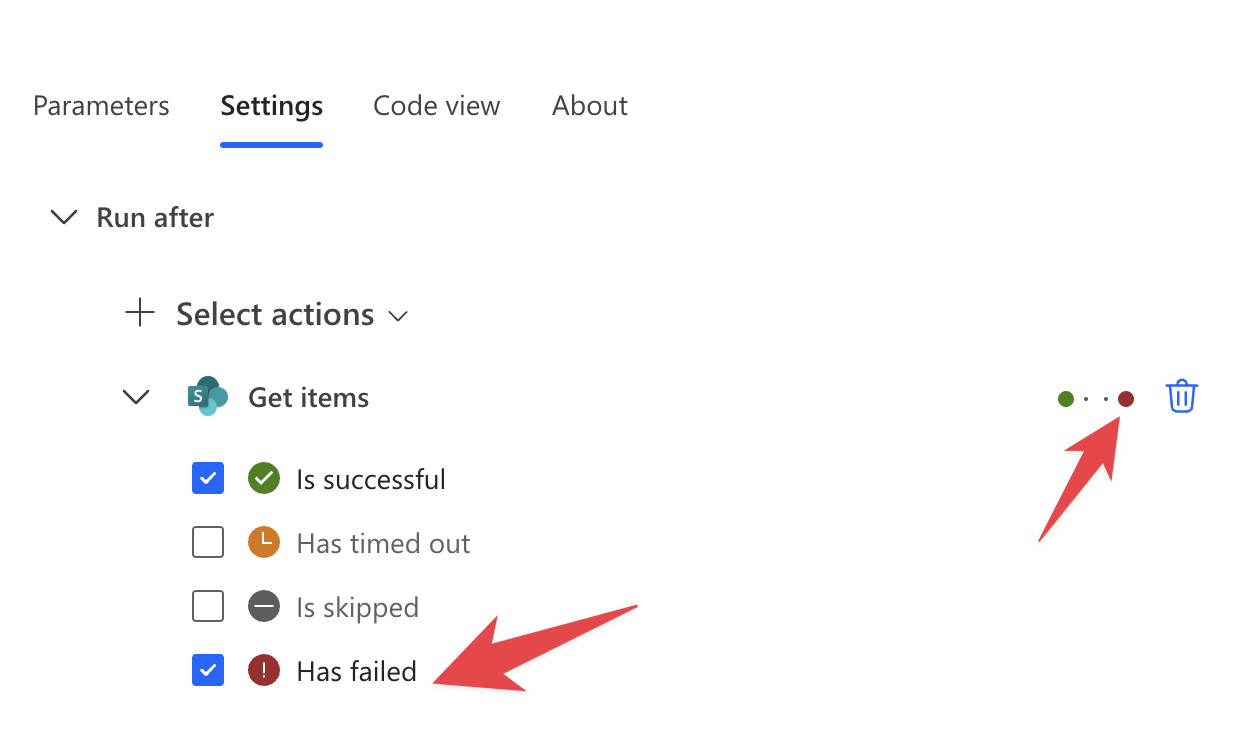

If you add “Has failed”, then the “Compose” Action will execute on both “Is successful” and “failed” states.

The trick here is to create the branching so that you can have a “path” for when things work fine and another one for when things fail. If you’re not familiar with branching in Power Automate here’s an article on how it works.

This feature enables patterns like try-catch blocks and ensures cleanup actions run regardless of whether main actions succeed, so let’s explore it.

Try-Catch-Finally Pattern

The try-catch-finally pattern uses scope actions to group operations and handle errors at the group level. This provides a cleaner flow structure and makes error-handling logic more maintainable.

Try Scope: Contains your main process actions—everything you want to accomplish in the happy path. If any action inside the try scope fails, the entire scope is marked as failed.

Catch Scope: Configured to run after the Try scope “has failed” or “has timed out.” Contains error-handling logic: log the error, send notifications, attempt recovery, or perform cleanup specific to failures.

Finally Scope: Configured to run regardless of whether Try succeeds or fails (run after “is successful” or “has failed”). Contains cleanup operations that must always happen: close connections, update status fields, or record completion.

This pattern makes error handling explicit and separates happy path logic from error handling code, improving flow readability significantly.

As I mentioned before, I have a template and go into a lot of detail in this article, so please check it out for more details.

Built-In Retry Policy

Power Automate includes automatic retry logic for transient failures, but it’s not enabled by default for all error types. You can customize the retry policy for each action through its settings.

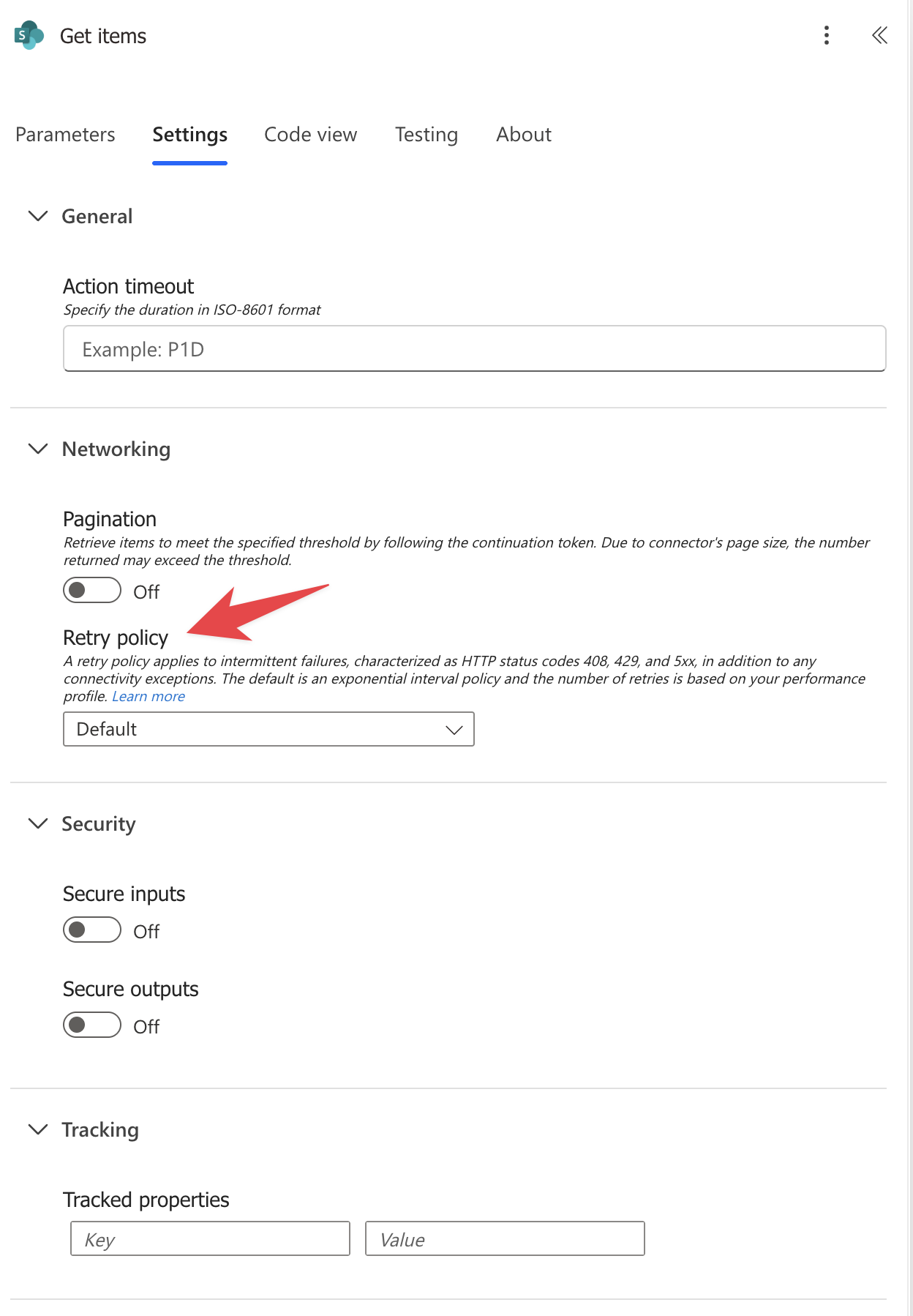

To configure retry policy, click the action, then pick “Settings” and “Retry Policy”.

If you expand you’ll get this:

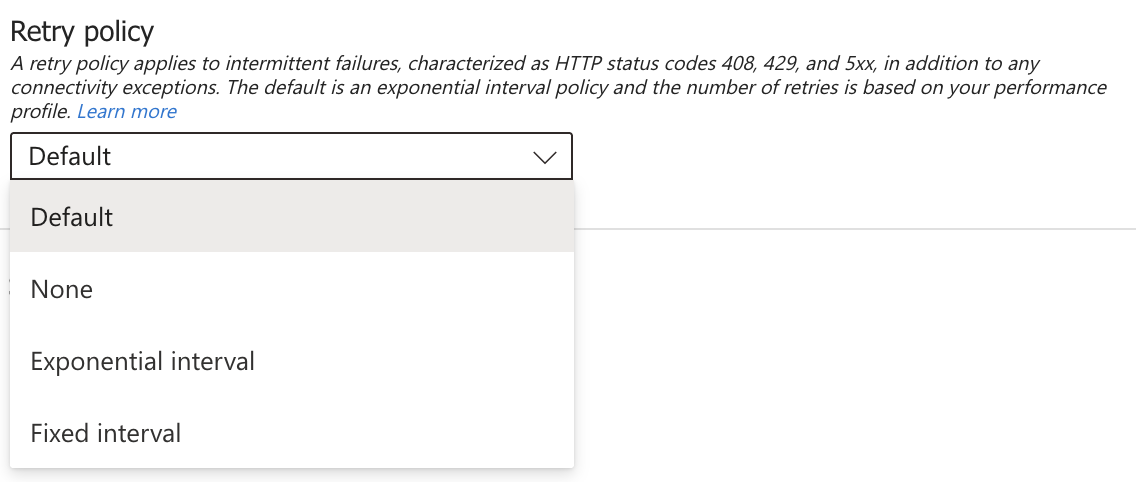

Let’s explore the policies.

None

Disable the retry policy altogether and fail right away. It’s not advisable since network issues occur all the time, so failing right away could only make sense in very strict environments.

Default configuration

Exponential interval, 2 retries for a 5-minute interval. Here’s the official documentation since these things could change quickly.

Applies to: HTTP 408 (timeout), 429 (too many requests), and 5xx (server errors)

Does not apply to 4xx errors (except 408 and 429), which are treated as permanent failures

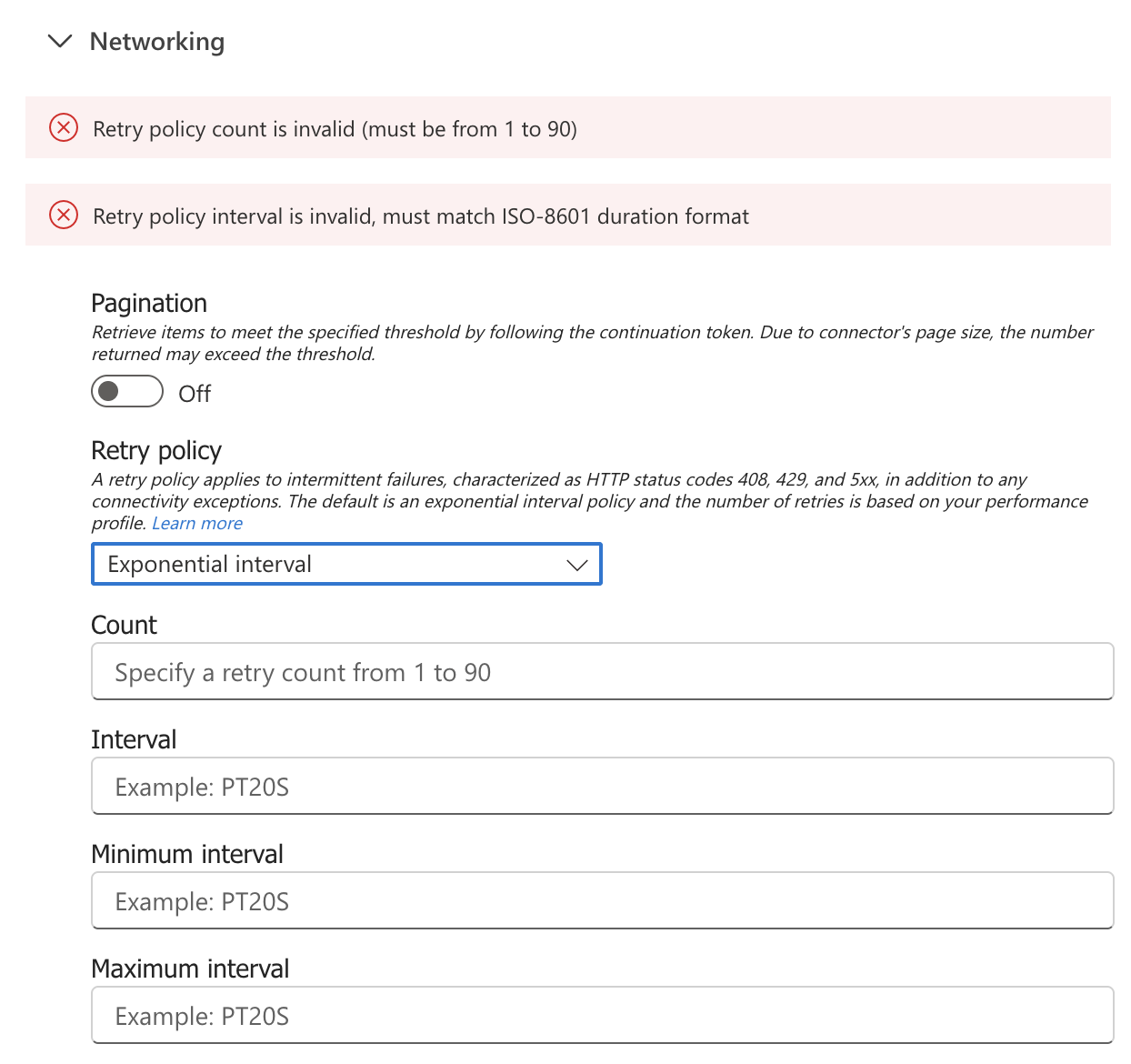

Exponential interval

Exponential interval defined by you. It will pick a random value between the min and max interval and will apply it with a modifier. Here are the settings, and I’ll explain the concept better later:

- Count – the max number it will try before failing

- Interval – Default interval to apply the delay

- Minimum interval – Min interval for the random value

- Maximum interval – Max interval for the random value

Exponential backoff is crucial for throttling scenarios. If SharePoint returns 429 “Too Many Requests,” you don’t want to immediately retry—that just makes the throttling worse.

Exponential backoff automatically increases the delay between retries, giving the service time to recover. Also, it introduces some random intervals, which is strange, but think about the case where you have multiple actions trying to access the same resource, like SharePoint, for example, and it rejects the calls. If all of them have the same retry policy, after the retry all of them will fail again. If we introduce slight variances to the time of the retry, then they will have a better chance of completing without getting errors.

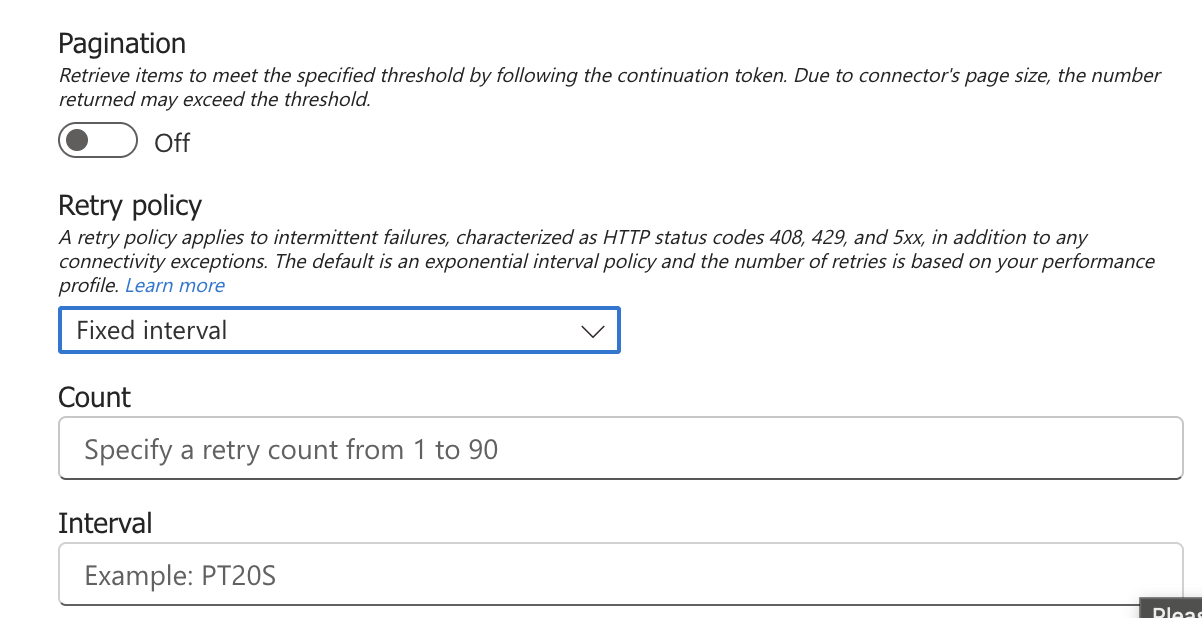

Fixed interval

Retry based on a fixed interval of time.

This won’t solve the previous issue of all trying to access the resource at the same time but could be useful in lower-priority flows where all you want is for the Flow to eventually finish.

Custom Retry with Do Until

For more control over retry logic, implement a custom retry loop using the “Do Until” action. This approach lets you check specific conditions, handle the “Retry-After” header from 429 responses, and implement custom recovery logic.

The pattern:

Do Until <success condition>

- Your action

- Condition: Is it failing (you can use branching)

- If Yes:

- Get Retry-After header value

- Delay for specified seconds

- If No:

- Check if status is 200 (success)

- If not 200 and not 429/503, terminate (permanent failure)

This pattern respects the service’s “Retry-After” guidance, doesn’t waste retries on permanent failures (4xx errors other than 429), and gives you full visibility into retry attempts, but it’s a lot more complex because it requires you to deal with the delays. Also, I don’t like using “Do Until” actions since I like to have as deterministic runs as possible, but I’m including it for the sake of completeness and to give you ideas.

Set an appropriate iteration limit on the “Do Until” action to prevent infinite loops if the action never succeeds.

Error Logging to an external system

When flows fail, you need diagnostic information to troubleshoot efficiently. The built-in run history helps (up until it’s gone), so creating a dedicated error log in SharePoint provides better long-term tracking and reporting. I’m showing you how to do it in SharePoint, you can do it in any database / system that you want as long as you can easily query the data after.

Create a SharePoint list with these columns:

- Flow Name: Which flow encountered the error

- Run ID: Links directly to the specific run

- Error Message: What went wrong

- Timestamp: When the error occurred

- User: Who triggered the flow

- Additional Context: Any relevant dynamic content that you want to store

You can use the “workflow” function to pick the information you want to save and then save it in your “database” of choice.

Final Thoughts

If you aren’t using these techniques, it’s not a problem. Knowing about them is the most important part. You can think about how to approach things on your side, like integrating some in your most important Flows or starting to test them in your new Flows.

My suggestion is to pick the most important Flows and start adding them slowly.

The idea is that you’re in control of what’s happening. If something fails, you can react automatically, even if it’s by doing something as simple as emailing you notifying you that the Flow failed.

It goes a long way to have Flows that work all the time vs Flows that fail and you only notice when someone else complains.

You can follow me on Mastodon (new account), Twitter (I’m getting out, but there are still a few people who are worth following) or LinkedIn. Or email works fine as well 🙂